Brisbane’s archive is based on the investigation of political holes that took over Brisbane under Premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen (1968-1987) whose government was famous for its electoral malpractices, and police corruption.1 Named the ‘Hillbilly Dictator’2, Bjelke-Petersen’s reign is important to the understanding of Queensland’s history from a social, political, and architectural level. From an architectural and urban perspective, Bjelke-Petersen’s administration was famous for their disregard of heritage buildings and how they championed a demolition agenda in Brisbane and Queensland generally. These state-wide demolitions were characterized by their spontaneity, nocturnal timings, and police accompaniment.3

Historian Rod Fisher estimated that over 60 significant buildings ‘bit the dust’ in Brisbane.4

The destruction of the city grew rapidly in 1986 with the lead up to Expo 88 located in the South Bank area. The demolished buildings ranged from hotels, social hubs, and residences torn down to make way for Bjelke-Petersen’s vision of putting Brisbane on the map.

What was particular about these demolitions was the way in which they were executed. The ‘nocturnal demolitions’ became a signature act of the Bjelke-Petersen administration.5 Aided by the demolition company The Deen Brothers, Brisbane’s buildings were demolished within minutes in the dead of night.6 For example, on the 21rst of April 1979 at midnight, a convoy of bulldozers under police guard were sent out to raze the Bellevue hotel.7 The demolition of the hotel was met with 700 protesters that realised what was occurring. The outrage brought forth by the violent and inconspicuous demolition was due to the importance the hotel played socially and on an urban level. The midnight demolitions were considered to be acts of vandalism against the city.8 The peculiar time of the demolition, as well as the need for police accompaniment, and the disregard of the population’s interests became a standard staple of some of these demolitions. The attack against the urban fabric was further emphasised through the Queensland parliamentary debates that considered the demolition blatantly illegal. As parliamentarian Terry Gygar argued:

…that this House condemns the precipitate and unannounced way the demolition of the Bellevue Hotel was commenced on the night of Friday, 20 April 1979.” In moving this motion, I emphasise to the House that it relates not to the fact that the building was demolished, not to the fact that it was pulled down-that is an entirely separate issue-but to the way in which it was pulled down, to the methods that were adopted and to the incidents that occurred on that night.9

The demolition of Cloudland, The Bellevue Hotel, Regent Theatre, and Trades’ Hall targeted the cultural sector, erasing cultural gatherings from the city. The social and cultural aspects of the city were eradicated further through the demolition of the artist area bounded by Roma, George, and Herschel Streets as mentioned previously. The demolitions that seemed to increase in 1982 and 1986 could suggest a deliberate extensive pattern of demolitions affecting the shared spatiality and social experience of the city amongst its residents that Coward emphasised as a symptom of urbicide. The targeting of these buildings led to a homogenization of the city where cultural spaces were no longer situated and were instead replaced by office or governmental buildings. It can thus, be argued that the Bjelke-Petersen administration erased part of the social history of the city and replaced it with corporate, and government developments. Consequently, the framing under urbicide stresses the attack against the social and cultural qualities of Brisbane city.

Building the archive

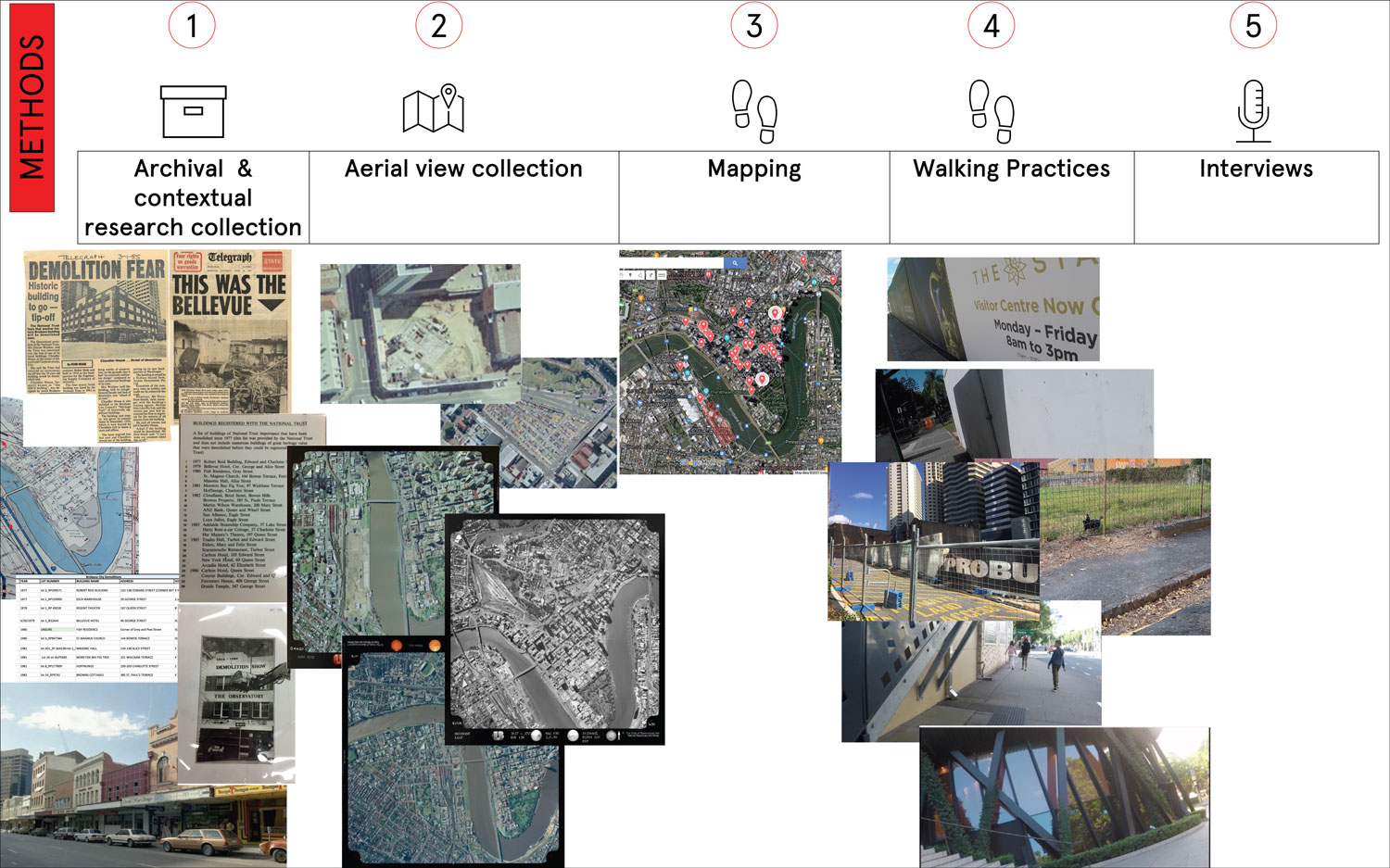

The research into the representation of the physical and psychological hole revealed first a lack of documentation of all the demolitions that occurred and a need to create one. By combining information gathered from aerial views, archival sources, and artist’s representations, a collection of political holes could be achieved. Through literature studies and archival studies relating to the physical hole, it became evident that there is a lack of mapping of demolitions. Consequently, the first step of the creative outputs consisted of finding these demolitions in order to compile them into a list. Built on newspaper clippings, the Queensland legislative assembly Hansard, curator John Stafford’s archive, and a study of aerial views, I have created a new list. The categories of the list were: demolished building’s name, year of demolition, address, function, and the lifespan of the hole. The characteristics were selected to be able to compare 1- the year in which the demolitions took place, 2- their function as a building, 3- the timeline for the political holes to reveal how long they remained within the urban fabric, 4- the function of the new building they were replaced by.

The archive traces the demolished building and their political holes. Based on the list of demolitions, digital mapping was created to locate the political holes. The map showed how the demolitions were spread out over the city while sometimes targeting specific areas such as Queen Street, Roma Street, and South Bank. Through the map, it was evident that most political holes no longer exist in the urban fabric and were replaced by buildings. Consequently, aerial views were collected from QImagery to note the changes in the political holes, and their duration in the city.

The archive lists the political holes chronologically. Each political hole is labelled after the demolished building’s name and reveals the specificities of each through its physical and psychological facets.

1 The Fitzgerald Inquiry conducted in 1987-89 investigated Bjelke-Petersen’s administration and concluded that it was institutionally corrupt.

2 Evan Whitton, The hillbilly dictator: Australia's police state (Crow’s Nest, N.S.W: ABC Enterprises for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 1989).

3 Rod Fisher, “'Nocturnal demolitions': the long march towards heritage legislation in Queensland,” Australian Historical Studies 23, no. 96 (1991).

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 John Wanna and Tracey Arklay, “All power corrupts, 1976–1980,” in The Ayes Have It, The history of the Queensland Parliament, 1957-1989 (ANU Press, 2010).

7 Fisher, “‘Nocturnal demolitions’”, 55.

8 Ibid, 56.

9 Queensland Parliament, Queensland Parliamentary Debates [Hansard] Legislative Assembly, (Queensland April 24, 1979). https://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/documents/hansard/1979/1979_04_24.pdf.